On June 18, dozens of community volunteers turned out to help Metro Blooms plant a raingarden at Riverside Plaza, a huge, high-density apartment complex in Minneapolis’ Cedar-Riverside neighborhood. They pulled on gardening gloves and received a short lesson on planting; within two hours, they had put in 477 plants, creating a beautiful green space that will provide pollinator habitat and help prevent water pollution. The success of the community planting event was due in great part to the efforts of climate stewards, resident volunteers, who promoted the event among their friends and neighbors. The climate stewards had been meeting with Metro Blooms for months to learn about sustainable landscaping practices and to participate in a redesign of Riverside’s outdoor spaces. This was the first raingarden installation.

This project is one of our most recent efforts to conduct our work within an equity framework based on environmental justice principles. Metro Blooms is known for providing sustainable design, installation, maintenance and education services to build resilient landscapes. But in the past three years we have started changing how we do this by extending our work beyond creating resilient landscapes to building resilience in communities. We try to leverage and enhance a community’s existing assets, building capacity as we improve the livability of the places where people live, work and play.

The Environmental Protection Agency ( EPA) defines “environmental justice” as “fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” This is the definition people recognize the most. A large component of environmental justice that is often neglected is equal access to the decision-making process when efforts are made to improve the environment. More often than not, people most affected by such decisions (including those with low incomes, people of color, recent immigrants, non-native English speakers and other historically marginalized groups) have been left out of the process. This is of particular importance now, as many of these communities are disproportionately affected by climate change.

Working with partners such as the non-profit African Career, Education, and Resource (ACER) and the Alliance for Metropolitan Sustainability, we have been developing a participatory education and engagement process surrounding the design, installation, and maintenance of clean water initiatives. We’re using the framework of a scorecard on equitable development from The Alliance, a Twin Cities coalition of organizations working towards equity. We have tailored this scorecard to our work through the development of an equitable engagement toolkit focused on building the capacity of communities to work towards clean water, helping us to understand issues such as disparity of engagement based on income and race, disproportionate access to green spaces, the risk of increased vulnerability to climate change factors in the existing environment and divestment of clean water funds in underserved communities.

We have used this equitable engagement process on two recent large-scale projects, each with its own distinct community and needs. The first one, Mercado Central, is a thriving marketplace of 35 businesses at the corner of Lake Street and Bloomington Avenue in Minneapolis. The second project is Riverside Plaza (mentioned in the first paragraph), an apartment complex with 11 buildings, over 1,300 units, and nearly 5,000 residents. This concrete structure with colored panels is a distinctive landmark that for many has come to symbolize the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood.

The objective at Mercado Central is to incorporate stormwater management practices on the site to treat runoff from the building and parking lot. The marketplace seeks to address flooding in the parking lot, add green space and beautify the property. Goals include partnering with local artists to create elements reflective of the Latin culture that are functional, like artist-created benches or decorative mosaics on garage bins. Marketplace vendors have attended meetings with Metro Blooms to take part in planning.

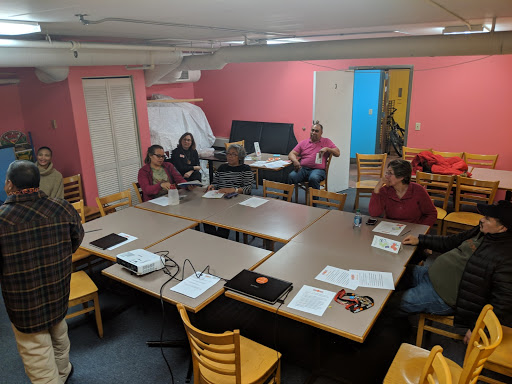

The objective at Riverside is to build capacity within the community by recruiting climate stewards from among the tenants who will lead their neighbors in being part of the work to improve their outdoor spaces. In addition, Sherman Associates, the owner of Riverside and of Autumn Ridge, another of our equitable engagement project sites, also wants to beautify and create a green space in an environment that is primarily concrete jungle.

In both cases, participatory landscape design puts the community at the center of decision-making. From the types of improvements that will be installed to the artwork that will be exhibited to the plants that will be chosen for the plaza, decisions will be discussed within the community before they are finalized. This helps strengthen relationships and build long-term trust with the community.

We will be sharing this work with others. We manage Blue Thumb, a public/private partnership that promotes ecologically functional landscapes to improve water quality. In our next meeting with Blue Thumb partners, we will discuss environmental justice and its importance in improving livability and resilience in all communities. Local government, private and community partners will provide feedback on our equitable engagement process at Autumn Ridge in Brooklyn Park, including a tour of newly-installed stormwater best management practices.

— Yordanose Solomone, Equitable Engagement Manager